https://monthlyreviewarchives.org/index.php/mr/article/view/MR-001-01-1949-05_3

TRADUCCIÓN ABAJO

Why Socialism?

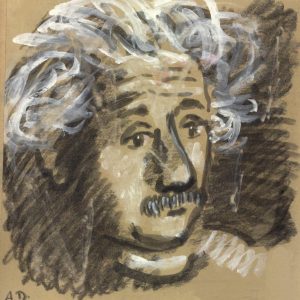

Albert Einstein (1959), charcoal and watercolor drawing by Alexander Dobkin. Dobkin (1908–1975) was an important painter of the mid-twentieth century American realist tradition along with other left-wing artists such as Jack Levine, Robert Gwathmey, Philip Evergood, and Raphael and Moses Soyer. A student and collaborator of the Mexican muralist Jose Clemente Orozco, his work is in the permanent collections of the Butler Art Institute, the Museum of Modern Art, the Brooklyn Museum, the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Library of Congress, and the Smithsonian Institution. (The preceding caption was written by John J. Simon, "Albert Einstein, Radical: A Political Profile," Monthly Review vol. 57, no. 1 [2005].)

Albert Einstein is the world-famous physicist. This article was originally published in the first issue of Monthly Review (May 1949). It was subsequently published in May 1998 to commemorate the first issue of MR‘s fiftieth year.

De: https://monthlyreview.org/2009/05/01/why-socialism/

Is it advisable for one who is not an expert on economic and social issues to express views on the subject of socialism? I believe for a number of reasons that it is.

Let us first consider the question from the point of view of scientific knowledge. It might appear that there are no essential methodological differences between astronomy and economics: scientists in both fields attempt to discover laws of general acceptability for a circumscribed group of phenomena in order to make the interconnection of these phenomena as clearly understandable as possible. But in reality such methodological differences do exist. The discovery of general laws in the field of economics is made difficult by the circumstance that observed economic phenomena are often affected by many factors which are very hard to evaluate separately. In addition, the experience which has accumulated since the beginning of the so-called civilized period of human history has—as is well known—been largely influenced and limited by causes which are by no means exclusively economic in nature. For example, most of the major states of history owed their existence to conquest. The conquering peoples established themselves, legally and economically, as the privileged class of the conquered country. They seized for themselves a monopoly of the land ownership and appointed a priesthood from among their own ranks. The priests, in control of education, made the class division of society into a permanent institution and created a system of values by which the people were thenceforth, to a large extent unconsciously, guided in their social behavior.

But historic tradition is, so to speak, of yesterday; nowhere have we really overcome what Thorstein Veblen called “the predatory phase” of human development. The observable economic facts belong to that phase and even such laws as we can derive from them are not applicable to other phases. Since the real purpose of socialism is precisely to overcome and advance beyond the predatory phase of human development, economic science in its present state can throw little light on the socialist society of the future.

Second, socialism is directed towards a social-ethical end. Science, however, cannot create ends and, even less, instill them in human beings; science, at most, can supply the means by which to attain certain ends. But the ends themselves are conceived by personalities with lofty ethical ideals and—if these ends are not stillborn, but vital and vigorous—are adopted and carried forward by those many human beings who, half unconsciously, determine the slow evolution of society.

For these reasons, we should be on our guard not to overestimate science and scientific methods when it is a question of human problems; and we should not assume that experts are the only ones who have a right to express themselves on questions affecting the organization of society.

Innumerable voices have been asserting for some time now that human society is passing through a crisis, that its stability has been gravely shattered. It is characteristic of such a situation that individuals feel indifferent or even hostile toward the group, small or large, to which they belong. In order to illustrate my meaning, let me record here a personal experience. I recently discussed with an intelligent and well-disposed man the threat of another war, which in my opinion would seriously endanger the existence of mankind, and I remarked that only a supra-national organization would offer protection from that danger. Thereupon my visitor, very calmly and coolly, said to me: “Why are you so deeply opposed to the disappearance of the human race?”

I am sure that as little as a century ago no one would have so lightly made a statement of this kind. It is the statement of a man who has striven in vain to attain an equilibrium within himself and has more or less lost hope of succeeding. It is the expression of a painful solitude and isolation from which so many people are suffering in these days. What is the cause? Is there a way out?

It is easy to raise such questions, but difficult to answer them with any degree of assurance. I must try, however, as best I can, although I am very conscious of the fact that our feelings and strivings are often contradictory and obscure and that they cannot be expressed in easy and simple formulas.

Man is, at one and the same time, a solitary being and a social being. As a solitary being, he attempts to protect his own existence and that of those who are closest to him, to satisfy his personal desires, and to develop his innate abilities. As a social being, he seeks to gain the recognition and affection of his fellow human beings, to share in their pleasures, to comfort them in their sorrows, and to improve their conditions of life. Only the existence of these varied, frequently conflicting, strivings accounts for the special character of a man, and their specific combination determines the extent to which an individual can achieve an inner equilibrium and can contribute to the well-being of society. It is quite possible that the relative strength of these two drives is, in the main, fixed by inheritance. But the personality that finally emerges is largely formed by the environment in which a man happens to find himself during his development, by the structure of the society in which he grows up, by the tradition of that society, and by its appraisal of particular types of behavior. The abstract concept “society” means to the individual human being the sum total of his direct and indirect relations to his contemporaries and to all the people of earlier generations. The individual is able to think, feel, strive, and work by himself; but he depends so much upon society—in his physical, intellectual, and emotional existence—that it is impossible to think of him, or to understand him, outside the framework of society. It is “society” which provides man with food, clothing, a home, the tools of work, language, the forms of thought, and most of the content of thought; his life is made possible through the labor and the accomplishments of the many millions past and present who are all hidden behind the small word “society.”

It is evident, therefore, that the dependence of the individual upon society is a fact of nature which cannot be abolished—just as in the case of ants and bees. However, while the whole life process of ants and bees is fixed down to the smallest detail by rigid, hereditary instincts, the social pattern and interrelationships of human beings are very variable and susceptible to change. Memory, the capacity to make new combinations, the gift of oral communication have made possible developments among human being which are not dictated by biological necessities. Such developments manifest themselves in traditions, institutions, and organizations; in literature; in scientific and engineering accomplishments; in works of art. This explains how it happens that, in a certain sense, man can influence his life through his own conduct, and that in this process conscious thinking and wanting can play a part.

Man acquires at birth, through heredity, a biological constitution which we must consider fixed and unalterable, including the natural urges which are characteristic of the human species. In addition, during his lifetime, he acquires a cultural constitution which he adopts from society through communication and through many other types of influences. It is this cultural constitution which, with the passage of time, is subject to change and which determines to a very large extent the relationship between the individual and society. Modern anthropology has taught us, through comparative investigation of so-called primitive cultures, that the social behavior of human beings may differ greatly, depending upon prevailing cultural patterns and the types of organization which predominate in society. It is on this that those who are striving to improve the lot of man may ground their hopes: human beings are not condemned, because of their biological constitution, to annihilate each other or to be at the mercy of a cruel, self-inflicted fate.

If we ask ourselves how the structure of society and the cultural attitude of man should be changed in order to make human life as satisfying as possible, we should constantly be conscious of the fact that there are certain conditions which we are unable to modify. As mentioned before, the biological nature of man is, for all practical purposes, not subject to change. Furthermore, technological and demographic developments of the last few centuries have created conditions which are here to stay. In relatively densely settled populations with the goods which are indispensable to their continued existence, an extreme division of labor and a highly-centralized productive apparatus are absolutely necessary. The time—which, looking back, seems so idyllic—is gone forever when individuals or relatively small groups could be completely self-sufficient. It is only a slight exaggeration to say that mankind constitutes even now a planetary community of production and consumption.

I have now reached the point where I may indicate briefly what to me constitutes the essence of the crisis of our time. It concerns the relationship of the individual to society. The individual has become more conscious than ever of his dependence upon society. But he does not experience this dependence as a positive asset, as an organic tie, as a protective force, but rather as a threat to his natural rights, or even to his economic existence. Moreover, his position in society is such that the egotistical drives of his make-up are constantly being accentuated, while his social drives, which are by nature weaker, progressively deteriorate. All human beings, whatever their position in society, are suffering from this process of deterioration. Unknowingly prisoners of their own egotism, they feel insecure, lonely, and deprived of the naive, simple, and unsophisticated enjoyment of life. Man can find meaning in life, short and perilous as it is, only through devoting himself to society.

The economic anarchy of capitalist society as it exists today is, in my opinion, the real source of the evil. We see before us a huge community of producers the members of which are unceasingly striving to deprive each other of the fruits of their collective labor—not by force, but on the whole in faithful compliance with legally established rules. In this respect, it is important to realize that the means of production—that is to say, the entire productive capacity that is needed for producing consumer goods as well as additional capital goods—may legally be, and for the most part are, the private property of individuals.

For the sake of simplicity, in the discussion that follows I shall call “workers” all those who do not share in the ownership of the means of production—although this does not quite correspond to the customary use of the term. The owner of the means of production is in a position to purchase the labor power of the worker. By using the means of production, the worker produces new goods which become the property of the capitalist. The essential point about this process is the relation between what the worker produces and what he is paid, both measured in terms of real value. Insofar as the labor contract is “free,” what the worker receives is determined not by the real value of the goods he produces, but by his minimum needs and by the capitalists’ requirements for labor power in relation to the number of workers competing for jobs. It is important to understand that even in theory the payment of the worker is not determined by the value of his product.

Private capital tends to become concentrated in few hands, partly because of competition among the capitalists, and partly because technological development and the increasing division of labor encourage the formation of larger units of production at the expense of smaller ones. The result of these developments is an oligarchy of private capital the enormous power of which cannot be effectively checked even by a democratically organized political society. This is true since the members of legislative bodies are selected by political parties, largely financed or otherwise influenced by private capitalists who, for all practical purposes, separate the electorate from the legislature. The consequence is that the representatives of the people do not in fact sufficiently protect the interests of the underprivileged sections of the population. Moreover, under existing conditions, private capitalists inevitably control, directly or indirectly, the main sources of information (press, radio, education). It is thus extremely difficult, and indeed in most cases quite impossible, for the individual citizen to come to objective conclusions and to make intelligent use of his political rights.

The situation prevailing in an economy based on the private ownership of capital is thus characterized by two main principles: first, means of production (capital) are privately owned and the owners dispose of them as they see fit; second, the labor contract is free. Of course, there is no such thing as a pure capitalist society in this sense. In particular, it should be noted that the workers, through long and bitter political struggles, have succeeded in securing a somewhat improved form of the “free labor contract” for certain categories of workers. But taken as a whole, the present day economy does not differ much from “pure” capitalism.

Production is carried on for profit, not for use. There is no provision that all those able and willing to work will always be in a position to find employment; an “army of unemployed” almost always exists. The worker is constantly in fear of losing his job. Since unemployed and poorly paid workers do not provide a profitable market, the production of consumers’ goods is restricted, and great hardship is the consequence. Technological progress frequently results in more unemployment rather than in an easing of the burden of work for all. The profit motive, in conjunction with competition among capitalists, is responsible for an instability in the accumulation and utilization of capital which leads to increasingly severe depressions. Unlimited competition leads to a huge waste of labor, and to that crippling of the social consciousness of individuals which I mentioned before.

This crippling of individuals I consider the worst evil of capitalism. Our whole educational system suffers from this evil. An exaggerated competitive attitude is inculcated into the student, who is trained to worship acquisitive success as a preparation for his future career.

I am convinced there is only one way to eliminate these grave evils, namely through the establishment of a socialist economy, accompanied by an educational system which would be oriented toward social goals. In such an economy, the means of production are owned by society itself and are utilized in a planned fashion. A planned economy, which adjusts production to the needs of the community, would distribute the work to be done among all those able to work and would guarantee a livelihood to every man, woman, and child. The education of the individual, in addition to promoting his own innate abilities, would attempt to develop in him a sense of responsibility for his fellow men in place of the glorification of power and success in our present society.

Nevertheless, it is necessary to remember that a planned economy is not yet socialism. A planned economy as such may be accompanied by the complete enslavement of the individual. The achievement of socialism requires the solution of some extremely difficult socio-political problems: how is it possible, in view of the far-reaching centralization of political and economic power, to prevent bureaucracy from becoming all-powerful and overweening? How can the rights of the individual be protected and therewith a democratic counterweight to the power of bureaucracy be assured?

Clarity about the aims and problems of socialism is of greatest significance in our age of transition. Since, under present circumstances, free and unhindered discussion of these problems has come under a powerful taboo, I consider the foundation of this magazine to be an important public service.

TRADUCCIÓN:

¿Debe quién no es un experto en cuestiones económicas y sociales opinar sobre el socialismo? Por una serie de razones creo que si.

Permítasenos primero considerar la cuestión desde el punto de vista del conocimiento científico. Puede parecer que no hay diferencias metodológicas esenciales entre la astronomía y la economía: los científicos en ambos campos procuran descubrir leyes de aceptabilidad general para un grupo circunscrito de fenómenos para hacer la interconexión de estos fenómenos tan claramente comprensible como sea posible. Pero en realidad estas diferencias metodológicas existen. El descubrimiento de leyes generales en el campo de la economía es difícil por que la observación de fenómenos económicos es afectada a menudo por muchos factores que son difícilmente evaluables por separado. Además, la experiencia que se ha acumulado desde el principio del llamado período civilizado de la historia humana --como es bien sabido-- ha sido influida y limitada en gran parte por causas que no son de ninguna manera exclusivamente económicas en su origen. Por ejemplo, la mayoría de los grandes estados de la historia debieron su existencia a la conquista. Los pueblos conquistadores se establecieron, legal y económicamente, como la clase privilegiada del país conquistado. Se aseguraron para sí mismos el monopolio de la propiedad de la tierra y designaron un sacerdocio de entre sus propias filas. Los sacerdotes, con el control de la educación, hicieron de la división de la sociedad en clases una institución permanente y crearon un sistema de valores por el cual la gente estaba a partir de entonces, en gran medida de forma inconsciente, dirigida en su comportamiento social.

Pero la tradición histórica es, como se dice, de ayer; en ninguna parte hemos superado realmente lo que Thorstein Veblen llamó "la fase depredadora" del desarrollo humano. Los hechos económicos observables pertenecen a esa fase e incluso las leyes que podemos derivar de ellos no son aplicables a otras fases. Puesto que el verdadero propósito del socialismo es precisamente superar y avanzar más allá de la fase depredadora del desarrollo humano, la ciencia económica en su estado actual puede arrojar poca luz sobre la sociedad socialista del futuro.

En segundo lugar, el socialismo está guiado hacia un fin ético-social. La ciencia, sin embargo, no puede establecer fines e, incluso menos, inculcarlos en los seres humanos; la ciencia puede proveer los medios con los que lograr ciertos fines. Pero los fines por si mismos son concebidos por personas con altos ideales éticos y --si estos fines no son endebles, sino vitales y vigorosos-- son adoptados y llevados adelante por muchos seres humanos quienes, de forma semi-inconsciente, determinan la evolución lenta de la sociedad.

Por estas razones, no debemos sobrestimar la ciencia y los métodos científicos cuando se trata de problemas humanos; y no debemos asumir que los expertos son los únicos que tienen derecho a expresarse en las cuestiones que afectan a la organización de la sociedad. Muchas voces han afirmado desde hace tiempo que la sociedad humana está pasando por una crisis, que su estabilidad ha sido gravemente dañada. Es característico de tal situación que los individuos se sienten indiferentes o incluso hostiles hacia el grupo, pequeño o grande, al que pertenecen. Como ilustración, déjenme recordar aquí una experiencia personal. Discutí recientemente con un hombre inteligente y bien dispuesto la amenaza de otra guerra, que en mi opinión pondría en peligro seriamente la existencia de la humanidad, y subrayé que solamente una organización supranacional ofrecería protección frente a ese peligro. Frente a eso mi visitante, muy calmado y tranquilo, me dijo: "¿porqué se opone usted tan profundamente a la desaparición de la raza humana?"

Estoy seguro que hace tan sólo un siglo nadie habría hecho tan ligeramente una declaración de esta clase. Es la declaración de un hombre que se ha esforzado inútilmente en lograr un equilibrio interior y que tiene más o menos perdida la esperanza de conseguirlo. Es la expresión de la soledad dolorosa y del aislamiento que mucha gente está sufriendo en la actualidad. ¿Cuál es la causa? ¿Hay una salida?

Es fácil plantear estas preguntas, pero difícil contestarlas con seguridad. Debo intentarlo, sin embargo, lo mejor que pueda, aunque soy muy consciente del hecho de que nuestros sentimientos y esfuerzos son a menudo contradictorios y obscuros y que no pueden expresarse en fórmulas fáciles y simples.

El hombre es, a la vez, un ser solitario y un ser social. Como ser solitario, procura proteger su propia existencia y la de los que estén más cercanos a él, para satisfacer sus deseos personales, y para desarrollar sus capacidades naturales. Como ser social, intenta ganar el reconocimiento y el afecto de sus compañeros humanos, para compartir sus placeres, para confortarlos en sus dolores, y para mejorar sus condiciones de vida. Solamente la existencia de éstos diferentes, y frecuentemente contradictorios objetivos por el carácter especial del hombre, y su combinación específica determina el grado con el cual un individuo puede alcanzar un equilibrio interno y puede contribuir al bienestar de la sociedad. Es muy posible que la fuerza relativa de estas dos pulsiones esté, en lo fundamental, fijada hereditariamente. Pero la personalidad que finalmente emerge está determinada en gran parte por el ambiente en el cual un hombre se encuentra durante su desarrollo, por la estructura de la sociedad en la que crece, por la tradición de esa sociedad, y por su valoración de los tipos particulares de comportamiento. El concepto abstracto "sociedad" significa para el ser humano individual la suma total de sus relaciones directas e indirectas con sus contemporáneos y con todas las personas de generaciones anteriores. El individuo puede pensar, sentirse, esforzarse, y trabajar por si mismo; pero él depende tanto de la sociedad -en su existencia física, intelectual, y emocional- que es imposible concebirlo, o entenderlo, fuera del marco de la sociedad. Es la "sociedad" la que provee al hombre de alimento, hogar, herramientas de trabajo, lenguaje, formas de pensamiento, y la mayoría del contenido de su pensamiento; su vida es posible por el trabajo y las realizaciones de los muchos millones en el pasado y en el presente que se ocultan detrás de la pequeña palabra "sociedad".

Es evidente, por lo tanto, que la dependencia del individuo de la sociedad es un hecho que no puede ser suprimido -- exactamente como en el caso de las hormigas y de las abejas. Sin embargo, mientras que la vida de las hormigas y de las abejas está fijada con rigidez en el más pequeño detalle, los instintos hereditarios, el patrón social y las correlaciones de los seres humanos son muy susceptibles de cambio. La memoria, la capacidad de hacer combinaciones, el regalo de la comunicación oral ha hecho posible progresos entre los seres humanos que son dictados por necesidades biológicas. Tales progresos se manifiestan en tradiciones, instituciones, y organizaciones; en la literatura; en las realizaciones científicas e ingenieriles; en las obras de arte. Esto explica que, en cierto sentido, el hombre puede influir en su vida y que puede jugar un papel en este proceso el pensamiento consciente y los deseos.

El hombre adquiere en el nacimiento, de forma hereditaria, una constitución biológica que debemos considerar fija e inalterable, incluyendo los impulsos naturales que son característicos de la especie humana. Además, durante su vida, adquiere una constitución cultural que adopta de la sociedad con la comunicación y a través de muchas otras clases de influencia. Es esta constitución cultural la que, con el paso del tiempo, puede cambiar y la que determina en un grado muy importante la relación entre el individuo y la sociedad como la antropología moderna nos ha enseñado, con la investigación comparativa de las llamadas culturas primitivas, que el comportamiento social de seres humanos puede diferenciar grandemente, dependiendo de patrones culturales que prevalecen y de los tipos de organización que predominan en la sociedad. Es en esto en lo que los que se están esforzando en mejorar la suerte del hombre pueden basar sus esperanzas: los seres humanos no están condenados, por su constitución biológica, a aniquilarse o a estar a la merced de un destino cruel, infligido por ellos mismos.

Si nos preguntamos cómo la estructura de la sociedad y de la actitud cultural del hombre deben ser cambiadas para hacer la vida humana tan satisfactoria como sea posible, debemos ser constantemente conscientes del hecho de que hay ciertas condiciones que no podemos modificar. Como mencioné antes, la naturaleza biológica del hombre es, para todos los efectos prácticos, inmodificable. Además, los progresos tecnológicos y demográficos de los últimos siglos han creado condiciones que están aquí para quedarse. En poblaciones relativamente densas asentadas con bienes que son imprescindibles para su existencia continuada, una división del trabajo extrema y un aparato altamente productivo son absolutamente necesarios. Los tiempos -- que, mirando hacia atrás, parecen tan idílicos -- en los que individuos o grupos relativamente pequeños podían ser totalmente autosuficientes se han ido para siempre. Es sólo una leve exageración decir que la humanidad ahora constituye incluso una comunidad planetaria de producción y consumo.

Ahora he alcanzado el punto donde puedo indicar brevemente lo que para mí constituye la esencia de la crisis de nuestro tiempo. Se refiere a la relación del individuo con la sociedad. El individuo es más consciente que nunca de su dependencia de sociedad. Pero él no ve la dependencia como un hecho positivo, como un lazo orgánico, como una fuerza protectora, sino como algo que amenaza sus derechos naturales, o incluso su existencia económica. Por otra parte, su posición en la sociedad es tal que sus pulsiones egoístas se están acentuando constantemente, mientras que sus pulsiones sociales, que son por naturaleza más débiles, se deterioran progresivamente. Todos los seres humanos, cualquiera que sea su posición en la sociedad, están sufriendo este proceso de deterioro. Los presos a sabiendas de su propio egoísmo, se sienten inseguros, solos, y privados del disfrute ingenuo, simple, y sencillo de la vida. El hombre sólo puede encontrar sentido a su vida, corta y arriesgada como es, dedicándose a la sociedad.

La anarquía económica de la sociedad capitalista tal como existe hoy es, en mi opinión, la verdadera fuente del mal. Vemos ante nosotros a una comunidad enorme de productores que se están esforzando incesantemente privándose de los frutos de su trabajo colectivo -- no por la fuerza, sino en general en conformidad fiel con reglas legalmente establecidas. A este respecto, es importante señalar que los medios de producción --es decir, la capacidad productiva entera que es necesaria para producir bienes de consumo tanto como capital adicional-- puede legalmente ser, y en su mayor parte es, propiedad privada de particulares.

En aras de la simplicidad, en la discusión que sigue llamaré "trabajadores" a todos los que no compartan la propiedad de los medios de producción -- aunque esto no corresponda al uso habitual del término. Los propietarios de los medios de producción están en posición de comprar la fuerza de trabajo del trabajador. Usando los medios de producción, el trabajador produce nuevos bienes que se convierten en propiedad del capitalista. El punto esencial en este proceso es la relación entre lo que produce el trabajador y lo que le es pagado, ambos medidos en valor real. En cuanto que el contrato de trabajo es "libre", lo que el trabajador recibe está determinado no por el valor real de los bienes que produce, sino por sus necesidades mínimas y por la demanda de los capitalistas de fuerza de trabajo en relación con el número de trabajadores compitiendo por trabajar. Es importante entender que incluso en teoría el salario del trabajador no está determinado por el valor de su producto.

El capital privado tiende a concentrarse en pocas manos, en parte debido a la competencia entre los capitalistas, y en parte porque el desarrollo tecnológico y el aumento de la división del trabajo animan la formación de unidades de producción más grandes a expensas de las más pequeñas. El resultado de este proceso es una oligarquía del capital privado cuyo enorme poder no se puede controlar con eficacia incluso en una sociedad organizada políticamente de forma democrática. Esto es así porque los miembros de los cuerpos legislativos son seleccionados por los partidos políticos, financiados en gran parte o influidos de otra manera por los capitalistas privados quienes, para todos los propósitos prácticos, separan al electorado de la legislatura. La consecuencia es que los representantes del pueblo de hecho no protegen suficientemente los intereses de los grupos no privilegiados de la población. Por otra parte, bajo las condiciones existentes, los capitalistas privados inevitablemente controlan, directamente o indirectamente, las fuentes principales de información (prensa, radio, educación). Es así extremadamente difícil, y de hecho en la mayoría de los casos absolutamente imposible, para el ciudadano individual obtener conclusiones objetivas y hacer un uso inteligente de sus derechos políticos.

La situación que prevalece en una economía basada en la propiedad privada del capital está así caracterizada en lo principal: primero, los medios de la producción (capital) son poseídos de forma privada y los propietarios disponen de ellos como lo consideran oportuno; en segundo lugar, el contrato de trabajo es libre. Por supuesto, no existe una sociedad capitalista pura en este sentido. En particular, debe notarse que los trabajadores, a través de luchas políticas largas y amargas, han tenido éxito en asegurar una forma algo mejorada de "contrato de trabajo libre" para ciertas categorías de trabajadores. Pero tomada en su conjunto, la economía actual no se diferencia mucho de capitalismo "puro". La producción está orientada hacia el beneficio, no hacia el uso. No está garantizado que todos los que tienen capacidad y quieran trabajar puedan encontrar empleo; existe casi siempre un "ejército de parados". El trabajador está constantemente atemorizado con perder su trabajo. Desde que parados y trabajadores mal pagados no proporcionan un mercado rentable, la producción de los bienes de consumo está restringida, y la consecuencia es una gran privación. El progreso tecnológico produce con frecuencia más desempleo en vez de facilitar la carga del trabajo para todos. La motivación del beneficio, conjuntamente con la competencia entre capitalistas, es responsable de una inestabilidad en la acumulación y en la utilización del capital que conduce a depresiones cada vez más severas. La competencia ilimitada conduce a un desperdicio enorme de trabajo, y a ése amputar la conciencia social de los individuos que mencioné antes.

Considero esta mutilación de los individuos el peor mal del capitalismo. Nuestro sistema educativo entero sufre de este mal. Se inculca una actitud competitiva exagerada al estudiante, que es entrenado para adorar el éxito codicioso como preparación para su carrera futura.

Estoy convencido de que hay solamente un camino para eliminar estos graves males, el establecimiento de una economía socialista, acompañado por un sistema educativo orientado hacia metas sociales. En una economía así, los medios de producción son poseídos por la sociedad y utilizados de una forma planificada. Una economía planificada que ajuste la producción a las necesidades de la comunidad, distribuiría el trabajo a realizar entre todos los capacitados para trabajar y garantizaría un sustento a cada hombre, mujer, y niño. La educación del individuo, además de promover sus propias capacidades naturales, procuraría desarrollar en él un sentido de la responsabilidad para sus compañeros-hombres en lugar de la glorificación del poder y del éxito que se da en nuestra sociedad actual.

Sin embargo, es necesario recordar que una economía planificada no es todavía socialismo. Una economía planificada puede estar acompañada de la completa esclavitud del individuo. La realización del socialismo requiere solucionar algunos problemas sociopolíticos extremadamente difíciles: ¿cómo es posible, con una centralización de gran envergadura del poder político y económico, evitar que la burocracia llegue a ser todopoderosa y arrogante? ¿Cómo pueden estar protegidos los derechos del individuo y cómo asegurar un contrapeso democrático al poder de la burocracia?

Comentarios